Moons

Andre Felipe

Earthlings will never know

The beauty of radiation-bathed sterility

The honesty of regolith, grey & dead

The virtue imposed by hard vacuum

They will sneer at moon people

Who starved the patriarchs to render them

Fertiliser, so we might have society.

They will call us “lunatics”

Not knowing the honour our cultures

Attach the word.

They will scan our poetry and say

We lack an eye for beauty

For we never had any.

We had the void, and darkness

Weaved its way into our dreams:

We mix moon-dust into our coffee.

We will insist they read our histories

And analyse our artefacts.

We lack metal for weapons

So we have none,

We lack patriarchs,

So we need none.

They will threaten fire-bombings

While we have no atmosphere.

The beauty of radiation-bathed sterility

The honesty of regolith, grey & dead

The virtue imposed by hard vacuum

They will sneer at moon people

Who starved the patriarchs to render them

Fertiliser, so we might have society.

They will call us “lunatics”

Not knowing the honour our cultures

Attach the word.

They will scan our poetry and say

We lack an eye for beauty

For we never had any.

We had the void, and darkness

Weaved its way into our dreams:

We mix moon-dust into our coffee.

We will insist they read our histories

And analyse our artefacts.

We lack metal for weapons

So we have none,

We lack patriarchs,

So we need none.

They will threaten fire-bombings

While we have no atmosphere.

I set out with the intent to write a poem about moons, satellites—in the natural sense of the word, the only sense until Man constructed some rickety amalgam of metal and shot it into space—because to me there is no more perfect symbol of possibility. The image of our moon, the airless sterility of its irradiated regolith surface, from the sterile beauty of immense flat fields of the lunar Maria to the vast collections of inconsistencies in the lunar terrain which pass for hills and mounds, all of it screams possibility. One day, perhaps there will be people there. Perhaps, there will be children growing up in air-tight, off-world-built enclosures. Perhaps, there will be poets. I can’t wait to read what they write. I wonder what they would think of my lunar poetry—how they would spit mid-verse, pointing at a particular line and saying oh, how close he is and yet how far, for he cannot know what I know.

![4 Galilean Moons by Space.com]()

My attachment to moons, borne out of a childhood infatuation with our own moon, itself was formed from the wealth of imagery inherited from millennia of writings on the moon. There is hardly an artist who denies its connection to their mythopoetic view of the world, and its singular beauty. I remembered reading lunar legends from different cultural contexts, and was always amazed at descriptions of the moon. The soft reverence which so many have held for the moon, how different it was from the beliefs and practices of solar-cults, all war-like and preoccupied with violence. But moon was a lover, not a warrior, and much more than that, she was a hunter.

In the Hellenic age It was christened “she” and revered as goddess, for whom the masses clamoured in names like Diana or Artemis.

In Amazonian myth, the romance of the moon and the sun threaten to destroy all life in the world. The sun scorched us, and the moon drowned us.

There is hardly a culture that has not recognised significance in the moon, significance worthy of story-telling, which means something truly significant. Anything about which stories are not written cannot be said to be important to our species, which is not (as genealogists have wrongly named it) the thinking man, “homo sapiens,” for who do you see doing much thinking these days? The significance of one was called virgin, lover, and traveler. Significance of one who today is the secular bringer of the tides, no longer Goddess, but Godly, and member of a curious kind.

I share in that historical obsession, and take it further to include a preoccupation with moons in general, as well as with our moon in particular. There are symbols for seven moons tattooed on my body (the five moons of Pluto, and Mars’ misshapen twins) Although, in what exactly, possibility may be found in Phobos, Triton, or Ganymede that Gaia is not privy to I am not so sure. Perhaps, it is possibility in the sense of the ability to choose differently, but I digress. I was born with my feet attached to the ground, what would I know?

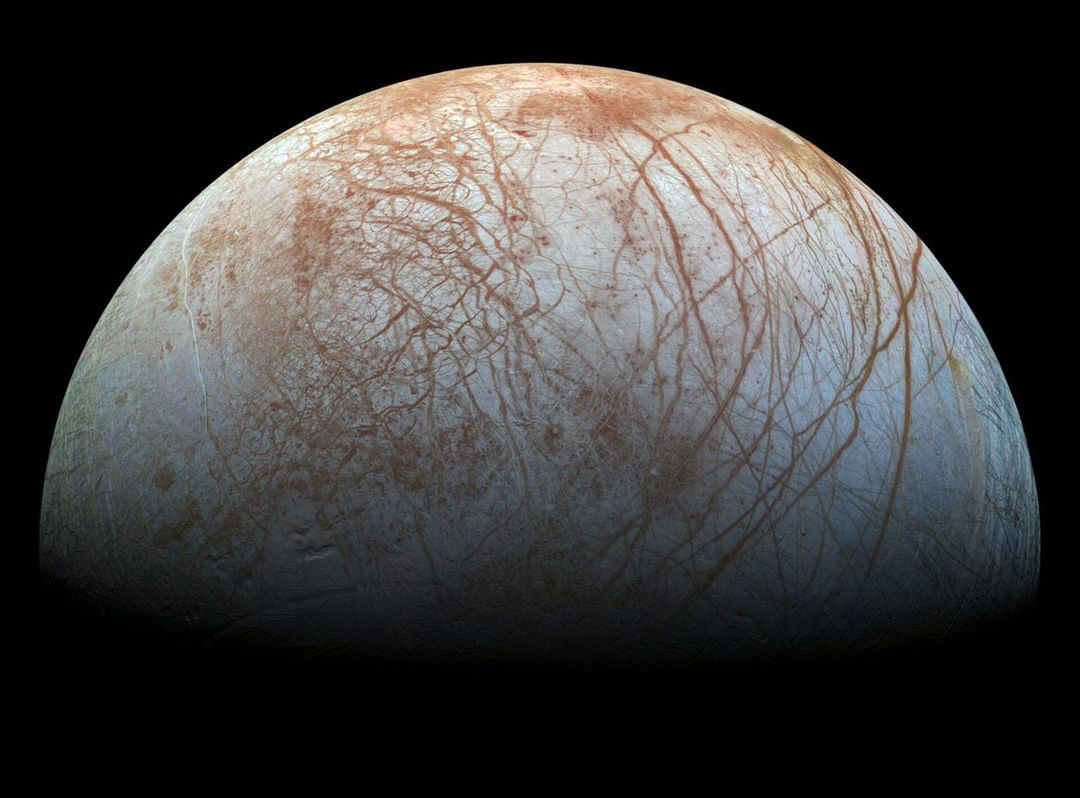

![Image of Europa by ESA]()

My attachment to moons, borne out of a childhood infatuation with our own moon, itself was formed from the wealth of imagery inherited from millennia of writings on the moon. There is hardly an artist who denies its connection to their mythopoetic view of the world, and its singular beauty. I remembered reading lunar legends from different cultural contexts, and was always amazed at descriptions of the moon. The soft reverence which so many have held for the moon, how different it was from the beliefs and practices of solar-cults, all war-like and preoccupied with violence. But moon was a lover, not a warrior, and much more than that, she was a hunter.

In the Hellenic age It was christened “she” and revered as goddess, for whom the masses clamoured in names like Diana or Artemis.

In Amazonian myth, the romance of the moon and the sun threaten to destroy all life in the world. The sun scorched us, and the moon drowned us.

There is hardly a culture that has not recognised significance in the moon, significance worthy of story-telling, which means something truly significant. Anything about which stories are not written cannot be said to be important to our species, which is not (as genealogists have wrongly named it) the thinking man, “homo sapiens,” for who do you see doing much thinking these days? The significance of one was called virgin, lover, and traveler. Significance of one who today is the secular bringer of the tides, no longer Goddess, but Godly, and member of a curious kind.

I share in that historical obsession, and take it further to include a preoccupation with moons in general, as well as with our moon in particular. There are symbols for seven moons tattooed on my body (the five moons of Pluto, and Mars’ misshapen twins) Although, in what exactly, possibility may be found in Phobos, Triton, or Ganymede that Gaia is not privy to I am not so sure. Perhaps, it is possibility in the sense of the ability to choose differently, but I digress. I was born with my feet attached to the ground, what would I know?

Though I suppose the writing may provide clarity to the Writer, the same way the Luna provides the tides to the Earth, the same way the Future provides a direction for the Past: as a natural and irresistible consequence of their relationship.

Perhaps, it is possibility found in alienness. The kind of alienness born from a sense of difference, whether the difference be slight or vast. Maybe, it is more impactful if the difference is slight. Then, the alienness becomes disconcerting, unsettling as if saying come, come and see my shores, and see that you were not chosen, you were just lucky. Returning to the point of the poem, I suppose I wanted to provide a sense of the intersection between moons’ alienness and possibility, to show that their possibility comes from their alienness, from their difference. If the fate, the development of cultures tied to the form nature takes in their particular context, what cultures would be reared on Luna’s airless sterility, on Triton’s frozen surface, or on Ganymede, with all its analogues to our Terran home.

Would they, for example, retain a sense of smallness and unimportance of their homes in the wake of the behemoths that dominate their horizon; what would they think of that hulking presence in their sky? What would they think of their ancestors, who inherited an Eden, boasting of a diverse biosphere, a breathable atmosphere, the liberty to inhabit most of the surface of the planet without extensive bio or traditional engineering solutions? Would they think of us at all? Or would they be occupied with new dreams? For their sake, I hope they are.

It did not us no good to inherit Eden, it taught us to take it for granted, we were tricked into calling it a place of material evil and taught to hate it and disregard it. Material evil, can you believe it? The Earth? While, elsewhere, just in Sol-system there are scenes of horror. Think of the sulphuric-acid rains of Venus; material evil. Reflect on the millennia-old, planet-wide storms on Jupiter; material evil. The abyssal darkness of Pluto; material evil.

![Luna by National Geographic]()

Moons are alien environments, and none of them are Eden. Some differ starkly from us, others not as much. But, make no mistake, none are Earth. And maybe, if we survive what we are doing to Earth, we will be able to populate these lesser heavens, less and nothing like cozy, dreamy Eden. Some will be sterile, airless. Some will have atmosphere, but it will be methane-filled, unbreathable to human lungs. Moons are filled with possibility because they are alien. They are filled with possibility because, in a certain sense, they are insignificant in the face of the behemoth’s gravity which bends their allegiance. Perhaps if our species is made to suffer alienness and insignificance, it will change us for the better. Maybe, hard vacuum will make us more caring. The moon’s tears would not drown the world then because moons would be worlds, homes. But never Eden, never Eden. It may be better that way.

Perhaps, it is possibility found in alienness. The kind of alienness born from a sense of difference, whether the difference be slight or vast. Maybe, it is more impactful if the difference is slight. Then, the alienness becomes disconcerting, unsettling as if saying come, come and see my shores, and see that you were not chosen, you were just lucky. Returning to the point of the poem, I suppose I wanted to provide a sense of the intersection between moons’ alienness and possibility, to show that their possibility comes from their alienness, from their difference. If the fate, the development of cultures tied to the form nature takes in their particular context, what cultures would be reared on Luna’s airless sterility, on Triton’s frozen surface, or on Ganymede, with all its analogues to our Terran home.

Would they, for example, retain a sense of smallness and unimportance of their homes in the wake of the behemoths that dominate their horizon; what would they think of that hulking presence in their sky? What would they think of their ancestors, who inherited an Eden, boasting of a diverse biosphere, a breathable atmosphere, the liberty to inhabit most of the surface of the planet without extensive bio or traditional engineering solutions? Would they think of us at all? Or would they be occupied with new dreams? For their sake, I hope they are.

It did not us no good to inherit Eden, it taught us to take it for granted, we were tricked into calling it a place of material evil and taught to hate it and disregard it. Material evil, can you believe it? The Earth? While, elsewhere, just in Sol-system there are scenes of horror. Think of the sulphuric-acid rains of Venus; material evil. Reflect on the millennia-old, planet-wide storms on Jupiter; material evil. The abyssal darkness of Pluto; material evil.

Moons are alien environments, and none of them are Eden. Some differ starkly from us, others not as much. But, make no mistake, none are Earth. And maybe, if we survive what we are doing to Earth, we will be able to populate these lesser heavens, less and nothing like cozy, dreamy Eden. Some will be sterile, airless. Some will have atmosphere, but it will be methane-filled, unbreathable to human lungs. Moons are filled with possibility because they are alien. They are filled with possibility because, in a certain sense, they are insignificant in the face of the behemoth’s gravity which bends their allegiance. Perhaps if our species is made to suffer alienness and insignificance, it will change us for the better. Maybe, hard vacuum will make us more caring. The moon’s tears would not drown the world then because moons would be worlds, homes. But never Eden, never Eden. It may be better that way.

Photos provided by the author

Cover by Katia